A Building Is a Business Model

What Midcentury Circle Ks Reveal About Reuse and Preservation

Before we begin, a disclaimer: This post was largely researched and at least half-written in a pre-covid world, making it as much an artifact of history as the buildings it attempts to critique. There are aspects that, while obscenely normal mere months ago, now betray some serious nostalgia (e.g. an evening beer run to the neighborhood corner store), and yet there are also observations I hope might read as more substantial when presented against the unstable backdrop of today's brave new world.

However empty they sit right now, our buildings have seen madness and market shocks before. They stand ready, as they always have, to adapt to however we might use them next, and some will adapt better than others. I suppose they are much like people in that respect.

The question I'm preoccupied with here is: Why? What makes one building more adaptable than another? Which will emerge from this crisis especially ready to live another lifecycle longer, sustained by business models that reflect a new era, even as they housed the models of decades past?

So that's where this is all headed, plus down to the corner store and back. If you're tired of feeling shut-in at home, then jump in and join me for the ride. -LL

"All we are is dust in the wind, dude."

-Ted Logan, 1989

It's 5:14pm on whatever day and the sun is headed west on McDowell Road, following it like a highway to the horizon. You're in the parking lot of a building that's a CBD-laced amalgam of packaged beer, vape pens, and glorious, made-to-order street tacos. Shadows stretch long across the asphalt and cars whiz-bang on by, as is their birthright in the pavement painted Phoenix valley.

To your left, just across the side street, there's a hand car wash backlit by the sunset and stark in silhouette. Men in denim dot the property. They hold towels and shift their weight from leg to leg, waiting around for the next dusty customer to pull in.

To your right, there's a low site wall parceling up the land. Out of the ground rises a tall, square sign and a palm tree just beside that's grown to maybe twice the sign's size. The sign is yellow, or so the sun makes it seem. It says 'Discount Food Market' and 'Deli & Smoke Shop.' The palm says nothing, but it streaks up against the sky, like a firework frozen mid-bloom.

The building is a single story of block and glass and deja vu—because you've seen it before, in other places, on other corners. It's stained with age, but it's there and it's working and people are going in and out and pushing and pulling the aluminum storefront door which ring-a-dings a faint bell that's hard to hear over all the rumbling of engines and whirling of wheels.

If you were a scholar who studies such things, you might count the building's peeling paint layers like tree rings. Or carbon date the exhaust that clouds its walls. Or set out door by door, knocking and introducing and small talking your way into an oral history of what the building once was, what it still is, and what it's meant to people all along.

But you probably won't do any of that, will you? Because you're just stopping through for a six-pack and the sun's gonna keep dropping like it does. You figure, what's the rush? Maybe you'll take a longer look next time. The building has been here, and surely the building will be here still. These sorts of things stick around, don't they?

And so you, too, are in and out with a ring-a-ding-ding, slipstreaming through traffic and home in time to hear the day grow tired of its own noise.

Almost Threescore and a Couple Uses Ago

"In an address to the annual convention of the American Institute of Architects in 1893, Barr Ferrce observed: Current American architecture is not a matter of art, but of business. A building must pay or there will be no investor ready with the money to meet its cost. This is at once the curse and the glory of American architecture."

-Carol Willis, Form Follows Finance, 1995

The building now home to the Discount Food Market on McDowell—at 1802 East, to be exact—was built in 1964, making it twenty-four years older than me and the same age as Keanu Reeves, a man who is, increasingly, a cultural bellwether against which we measure all things. 1802 East McDowell was born a Circle K Market in a time when Circle K Markets were shiny and new and infused with the booming optimism of yesterday's post-war suburbia, rather than the woke cynicism of today's end-stage capitalism. Years later it would become what it is now, an aging body with a new soul, a transfigured business model with a new name.

Buildings go through cycles in this way. They change, and they adapt. Because when they don't, they disappear. A storied few adapt loudly, in full view of neighbors and often in spite of much rigmarole. As prominent historic markers, jammed full of meaning and memory, they attract headlines, capture imagination, and inspire debate.

The Discount Food Market isn't in that kind of building. It's in the quieter kind, more background than foreground. A humble masonry box whose architecture, if you even think to call it that, is outweighed by scaled-up signs and vinyl banners. It's not the sort of building most people think to celebrate or about which preservation activists care to gossip. But it is the sort of building that's all over the place, the sort of building that’s too stubborn to be knocked down, where everyday stories start to add up to a life well-lived.

1802 East McDowell's entry into the public record didn't start at a public groundbreaking with gold shovels and spotless hardhats like the loud buildings do. Instead, it made news on April 2nd, 1965, maybe a year or so after it first opened, when a "nervous gunman wearing a black cowboy hat took $35 in a holdup."[1]

Over the next couple decades, the Arizona Republic reported no fewer than eleven additional holdups. It also had a brief cameo in the foiling of a bank robbery by a "crime-fighting cabbie,"[2] the mistaken sale of identical lottery tickets that won one lucky woman the same prize twice,[3] and the story of a Bible-reading store clerk who miraculously survived a gunshot to the head, played dead while $45 was taken from the register, and then, finding the store's phone out of order, attempted to drive himself to the hospital.[4] So if the place was ever a scene at all, it was as the scene of a crime.

That the convenience chain survived this sort of mischief and mayhem was a testament to the resilience of neighborhood demand for on-the-go groceries, refined sugar, and the occasional pre-packaged vice. But by the late '80s, about the time Ted "Theodore" Logan and Bill S. Preston, Esq. stepped into a time-traveling phone booth in the parking lot of another Phoenix-area Circle K, the demands of the market would change, and the mortgage bill, ever inevitable, would come due.

Against the moral objection of Cannie Martin and Reverend W. W. Thompson, Arizona's first Circle K was built sometime before the summer of 1957 at the northeast corner of Roosevelt and 16th St (Ms. Martin and the Reverend were offended by its proposed liquor sales, not, in some prescient warning, its trend-setting contribution to car-dependent suburbia).[5]

By September, the Arizona Republic advertised Circle K Drive-In Food Stores as "something new for Phoenix!" with "four locations for your convenience... open 7am to 11pm!... 7 days a week!!"[6] The drive-in market was a relatively new-fangled idea, one particularly well-suited to its era. Propelled by Phoenix's post-war expansion (from 1950-1960 the sun-drenched city grew by 4x in population and nearly 11x in size), Circle K couldn't close hard corner lands deals fast enough.

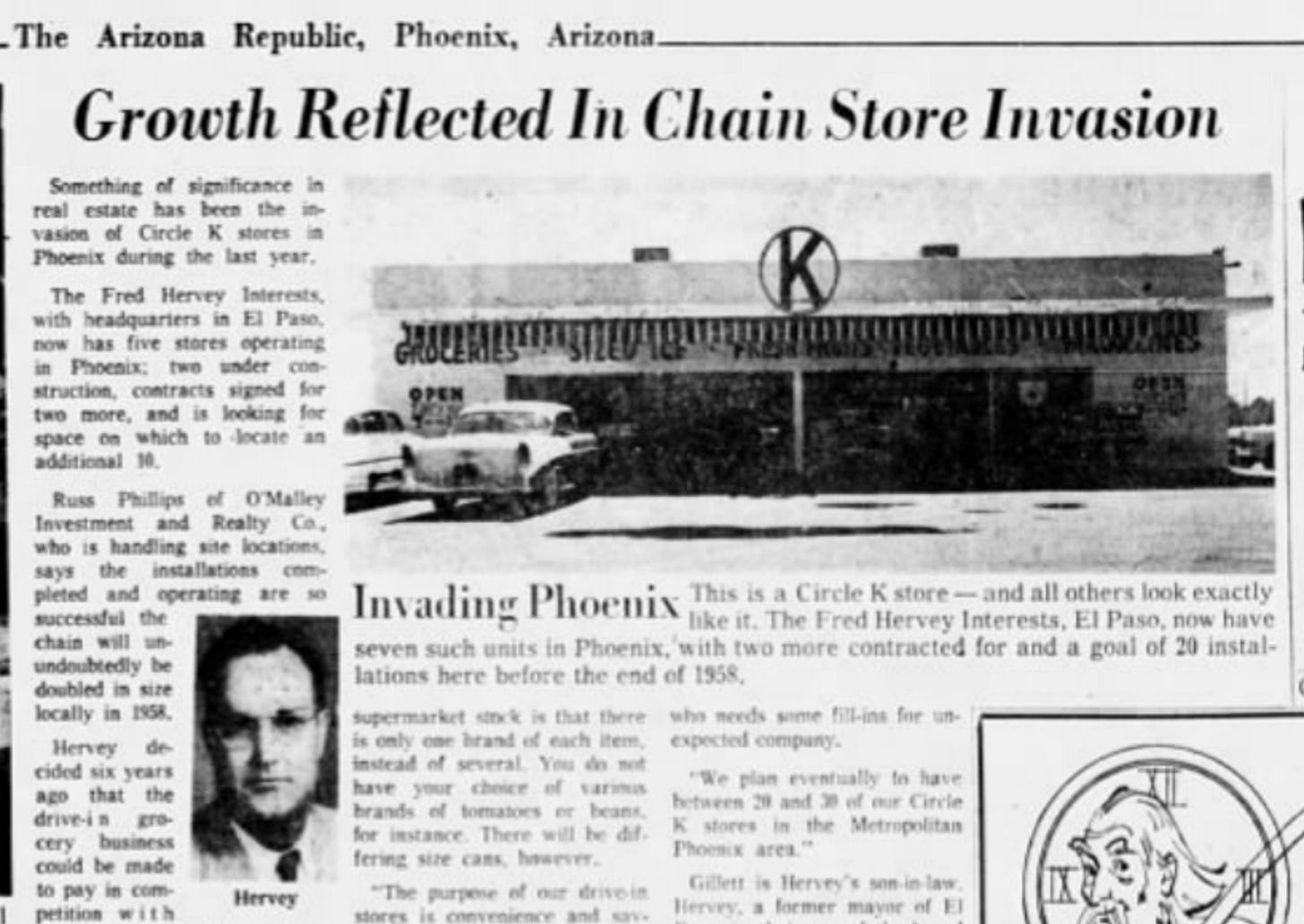

"Something of significance in real estate has been the invasion of Circle K stores in Phoenix during the last year," wrote the Republic in late 1957. "[They] now have seven such units in Phoenix, with two more contracted for and a goal for twenty installations here before the end of 1958."[7]

In today's world of extended permit review, heated neighborhood meetings, and heightened construction costs, building twenty of anything in a year sounds improbably ambitious, but amidst the booster-backed optimism of midcentury America anything seemed possible.

When their Phoenix foray kicked off, Circle K was a relatively small, family-run business, but they were a small, family-run business with visions of venture-scale grandeur. Every "unit" was built for one purpose: leverage, recoup, and recycle capital. To minimize fuss and maximize efficiency, "each store [was] exactly the same size and design. 40x60 feet. All painting and signs [were] exactly alike. All [had] open fronts."[8]

Betrayed by their investment-conscious design, these Circle K boxes were suburban manifestations of what real estate historian Carol Willis calls "vernaculars of capitalism" in Form Follows Finance, her behind-the-scenes look at the business models that shaped iconic 20th-century skyscapers like the Empire State Building. Similar to Willis’ towers, which she demonstrates to be speculative products whose "economics [were the] chief determinants of form," Circle K's midcentury buildings were a financial bet in time and space, a four-sided business model with a front door, pragmatically designed to replicate site selection, simplify construction, and attract revenue as quickly as possible. [9]

Unlike Willis' iconic skyscrapers, however, the typical Circle K box was largely unadorned, lacking a remarkable architectural facade. Stripped down and streamlined, they were the pursuit of profit in even starker and more obvious terms, a hyper-rational exploitation of post-war Phoenix's budding exuberance for sprawl. Where the vertical "formulas of finance [Willis studied] responded to the particular urban conditions of New York and Chicago," Circle K responded in turn to the horizontal calculus of an ever-expanding Phoenix. [10]

A midcentury Circle K at 2098 W. Bell Road, shown here in 1969 and then 1986. Many were built just ahead of growth, true masterpieces of suburban speculation, the aptly-named “last harvest” of ag land turned subdivision.

Whatever ornament they afforded was tacked on with a wink and a nod, recalling the "decorated shed" described by Venturi, Brown, and Izenour in Learning From Las Vegas' unrepentant ode to roadside architecture. In their book, the trio "acknowledge the validity of commercial architecture," detailing the aesthetic logic of a "roadside eclecticism" that values "communication over space" and applies "words and symbols...for commercial persuasion."[11]

"The building itself is setback from the highway and half hidden, as is most of the urban environment, by parked cars," writes Venture, Brown, and Izenour of the modern suburban supermarket. "The vast parking lot is in front, not at the rear, since it is a symbol as well as a convenience. Architecture defines very little: The big sign and the little building is the rule of Route 66."[12] 99% Invisible, the obscenely insightful design podcast produced in sunny, downtown Oakland, California, sums up decorated sheds this way: “generic structures with added signs and decor that denote their purpose.”

The Circle K box finds its basis in this pragmatic logic, albeit as an early, experimental predecessor to the all-out supermarket, its more-or-less-neighborhood-accessible scale somewhere smack between human and auto. To stand out, each of the earliest buildings came to replicate two distinctive traits: 1. A sloped roofline with repeating beams cantilevered over the storefront like a single, flightless wing (boldly threatening, as so many midcentury designs do, to send rainwater racing back toward the building), and 2. A tall, square sign at the property’s corner. These were the decorations on the shed, cost-effective ornaments applied to the site as a way to communicate and persuade.

This combination of site selection and design, sensibly optimized, minimally adorned, and shrewdly timed, proved effective. Just seven years after entering the Phoenix market, eighty-four Circle K's dotted street corners across the Valley.[13] Twenty stores a year, once ambitious, was simply business as usual by the mid-1960s.

1802 E McDowell, looking northeast from the all-seeing Eye of Sauron (aka the Google-mobile). Its projected overhang and square sign remain in good shape. Note the vinyl banner hung from the projection’s facia, a humble, low-cost attempt at ‘commercial persuasion.’

Ultimately though, Circle K's "chain store invasion" proved unsustainable—at least in its original form. After years of lending-fueled expansion and mixed-results fighting off the rise of vertically-integrated competition, the Circle K Corporation filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1990. The New York Times reported in mid-May of that year that "debt outstanding at the time of the filing was $1.1 billion." By December of '91, the fallout was clear. The company announced plans to "shut or sell more than 1,500 of its 3,700 stores" as it worked to emerge from bankruptcy a "leaner, stronger, more efficient company." [14]

Having reached the end of its useful economic life, the Circle K Market at 1802 East McDowell Road found itself among those 1,500 unprofitable souls paraded past shareholders to the corporate guillotine. It was shuttered by the mid-90s, its building left vacant, a depreciated husk shed back into the speculative world of commercial real estate, a space for somebody else to figure out, an expense for some other entity to take on.

In the end, it lived almost thirty years, dying a victim to men in suits, not ski-masks, a casualty not of bullets, but of bankers.

Strange Things Afoot

"Under capitalism there is, then, a perpetual struggle in which capital builds a physical landscape appropriate to its own conditions at a particular moment in time, only to have to destroy it, usually in the course of a crisis, at a subsequent point in time. The temporal and geographical ebb and flow of investment in the built environment can be understood only in terms of such a process. "

-David Harvey, The Urban Experience, 1985

In The Geography of Capitalist Accumulation, a 1975 essay that manages to both draw on Karl Marx and read like a page torn from Circle K's unrepentant corporate playbook, economic geographer David Harvey observes that "capitalist development has to negotiate a knife-edge path between preserving the values of past capital investments in the built environment and destroying these investments in order to open up fresh room for accumulation."

This reliable rhythm of rise and fall, where capital expands at-risk in an effort to compound and later contracts in response to falling profits or changing priorities, is a cyclical crisis that Harvey considers central to Marx's "theory of growth under capitalism." Investments anchored in space, like those tied to real estate and its associated functions and physical improvements, are especially susceptible to this boom and bust cycle, as anyone with a mortgage and a memory well knows.

Harvey, Marx, and Circle K’s early-90s bankruptcy remind us that despite the socio-cultural patina that often comes to soften a building's hard edges—thereby endearing it to later generations—a commercial structure is first and foremost an economic engine. "This insistence on the linkage between profit and program is fundamental to commercial architecture, where the function of a building is to produce rents, and economic considerations govern design decisions,” writes Carol Willis.[15]

Simply put, a building needs a business model, and that business model, finding perpetual motion thwarted by physics, is no more immune to entropy than the rest of us. It's hardwired with a decay function whose downward slope is influenced by volatile inputs like management prowess, consumer preferences, and market trends.

Given all that besieges buildings, everything from the economic to the meteorological, it is a wonder that any stay standing at all, but stand some do. In 2015, the U.S. Energy Information Administration reported that the median commercial building in the United States was thirty-two years old. The mountain west subset, adolescent by east coast standards, weighed in a few years shy at a median age of twenty-nine years. Only one-quarter of commercial buildings surveyed nationwide made it to fifty years or older, the best of them adaptable in the face of change.

To beat the median, a property owner must work against the clock to sustain, reinvent, or recruit a viable business model. That makes entrepreneurship the beating heart of any serious effort to scale the preservation and reuse of aging buildings—because no one preserves more buildings than small business owners.

But what makes one commercial building more adaptable than another? What do the odds-beating survivors offer entrepreneurs that others do not? For that, we return to the grizzled wisdom of the Circle K down the street.

Personages of Historic Significance

All building are predictions. All predictions are wrong.

-Stewart Brand, How Buildings Learn, 1994

In the early 2000s, an old Circle K caught the eye of art student and eventual Arizona State MFA grad Paho Mann. Over the course of the next decade, they grew into something of a creative obsession. Using archived city directories and old yellow pages (the sort of urban history lore that makes preservationists weak at the knees), Mann went Circle K hunting. Ultimately, he documented 178 early Phoenix-area locations, noting sometime in the late 2000s whether they were still in active use by the convenience store chain, operating as a new business, or demolished. Mann was especially fascinated by what he called the “re-inhabited Circle Ks,” the same ones that captivate me, where “small local businesses set up shop in locations that the corporation had abandoned [over] the past two decades.”[16] Much to my delight, he immortalized his fascination with a color-coded google map and a photo series you should absolutely click thru to see.

My fascination with Mann’s Circle K research also developed into a creative obsession, like a curse passed down through generations. Because I prefer tedious data entry to sleep, I Cntrl + Ced Mann’s list and then went line by line and address by address to update each entry circa Q1 2020. Using a combination of historical aerials, county assessor records, and Google maps/streetview, I set out to answer two primary questions: 1. How has each property’s status and use changed since the late-2000s, and 2. Approximately what year was each building built?

Here’s a Google sheet with what I found.

In some cases, county assessor records were clearly confused (and confusing), having apparently coded the year of some subsequent remodel as the year a building was constructed. In these cases, the earliest possible aerial was used to approximate age, courtesy of Maricopa County’s online GIS tools. Google streetview archives also helped a great deal. In the end, some coding decisions were a sort of squint-at-your-laptop-screen gut approximation, making my methods imperfect, but when it comes to data you do the best you can with what you’ve got. If you comb through and find anything that needs updating, let me know in the comments below or @urbnist on Twitter. For me, it is a living document and an ongoing quest.

Out of 174 early era Circle Ks that made my revised list, 126 still stand today, representing a loss of at least eleven units since Mann completed his list over a decade ago. At that slow-drip rate of demolition, eleven a decade, we’ll lose the last of them in about 120 years.

The 126 survivors break down like this: Seven are vacant and in some state of transition, twenty-two are still in use as Circle Ks (compared to thirty-five when Mann published his data), and ninety-seven have been adapted to new uses (“re-inhabited” in the parlance of Mann’s analysis; I elected to adopted his terminology, finding re-inhabited quaint and “destroyed” far more epic than the emotionless “demolished”). Some of the ninety-seven, such as 1802 E McDowell, remain relatively untouched, some have been tinkered with, and some have been heavily modified, all depending on the needs and whims of subsequent small businesses. The median age of the still-standing subset is roughly fifty-one years, but many are approaching sixty.

In a region where the typical commercial building is twenty-nine, Phoenix’s midcentury Circle Ks have proven especially robust. Perhaps more impressive, these buildings have by and large stood the test of time amidst a city many critics lament for its longstanding demolition culture.

The immediate question is why. No one is rushing to protect these buildings in place with a historic zoning overlay. No one is really leveraging preservation-related tax subsidies or state-backed incentives to make them pencil. And no one is rushing down to city hall with a petition to delay their impending demo permit each time it comes up.

So short of all that, what makes the midcentury Circle K especially durable and adaptable?

I’ve got three potential answers to that question, but mostly it comes down to the fact that these buildings have made themselves useful, and so the market has rewarded them with reuse.

The (small) rectangle lends itself to change

Consider for a moment that there exists an orderly spectrum of suburban building types—horizontal manifestations of Willis’ “vernaculars of capital”—replicated across American cities through the power and might of institutional-scale finance. Just as vernacular homes or low- to mid-rise downtown structures embody centuries of learning about what it takes to build and sustain an urban environment, so too have these vernaculars of capital spent the post-war era tweaking, fine-tuning, and experimenting their way toward a singularly guiding outcome: return on investment.

This spectrum includes now common building forms such as the drive-up convenience market, of which Circle K was an early innovator and corporations like Dollar General have now taken to its logical, profit-extracting conclusion, the hard corner all-in-one pharmacy (CVS and Walgreens being classic, warring examples), the big-box anchored retail strip (may it rest in peace), and, in our latest over-scaled ambition, the netted-just-off-the-interstate-entertainment-centers of Top Golf.

Circle K’s end of the spectrum, a little smaller and little less specialized, has proven itself more adaptable. In his must-read book How Buildings Learn, Stewart Brand “assembl[es] what might be called steps toward an adaptive architecture,” and that adaptive architecture is often comprised of right angles. [17]

He writes, “As for shape: be square. The only configuration of space that grows well and subdivides well and is really efficient to use is the rectangle… If you start boxy and simple, outside in, then you can let complications develop with time, responsive to use. Prematurely convoluted surfaces are expensive to build, a nuisance to maintain, and hard to change." [18]

The Circle K rectangle is Brand’s maxim brought to life. It has proven itself responsive to use, truly a blank slate, its Goldilocks floorplate (not too shallow, not too deep) just right to be remixed in dozens of different ways, including but not limited to this laundry list: auto sales, auto repair, title loans, insurance office, various brands of competing cell phone carriers, flower shop, liquor store, majrijuana dispensary, financial planning, payday lending, independent neighborhood market, fabric store, fitness gym, paint store, laundromat, dry cleaners, carniceria, burger joint, pizza place, Mexican food, print shop, tire store, deli, smoke shop, oxygen therapy for after the smoke shop, pet grooming, and a tattoo parlor.

Phoenix Flowers at 5018 W. Northern Avenue.

Econowash at 2301 N. 32nd Street.

Broadway Food and Meat Market at 2001 E. Broadway Road.

Boost Mobile at 3434 W. Peoria Avenue.

Approachable in both size and shape, it’s easy to see why so many different buildings find old Circle K’s immediately (and profitably!) useful. But the further you go down the spectrum of suburban building types, the bigger a building grows and the increasingly specialized its initial program becomes, the more difficult it gets to imagine an outcome that ends in anything but demolition. Taking on a 2,500 square feet Circle K box is one thing. But how will we take on a three-story Top Golf after it reaches the (inevitable) end of its run in twenty years? Its sheer scale and custom layout would complicate any attempt at adaptive reuse, and commercial proformas don’t deal well with complicated. Fortunately for them, the reuse question is one Top Golf probably won’t have to answer, especially if they wash their hands of it and follow the Circle K model to greener, post-bankruptcy pastures.

The ornament is inexpensive to modify and easy to customize

The thing about a nicely decorated shed is that every new owner wants to change the decorations. But on buildings like the early Circle Ks, the decorations lend themselves to modification, making them all the more attractive to would-be users who need their space to communicate purpose and advertise use without an unworkable amount of fuss or expense.

Ana’s Garden at 5419 S. Central Avenue. Sometimes a customized facade is as simple as hanging a branded banner, something any small business could do.

Bridgett’s Last Laugh at 17222 N. Cave Creek Road. Part dive bar, part comedy club, Bridgett’s elected to give themselves a little more room for signage and knick-knacks by building a facia off the front of their original overhang. Believe it or not, there’s a midcentury detail buried in there somewhere.

Bridgett’s entry in profile, its sloped beams still visible. Many of the remaining Circle K’s have had their overhang covered up in this way.

Beer Wine Smoke at 6024 N. 23rd Avenue. One of the more magical transformations, complete with new framing built up above the historic overhang, as well as a drive-thru lane punched right through the building. This one gets points for imagination.

Llantera Tire Shop at 3531 W. Bethany Home Road. If you squint, you can see the remnants of the iconic old beams just poking through an addition to the front of the former Circle K, no doubt changing the building such that it would be deep enough to comfortably accept vehicles.

Virginia Market at 702 E. Virginia Avenue. This one is my personal favorite, and not just because it houses a craft beer market. Here a wild and creative series of terraced 2x8s have been added above the original roofline. I once asked the guy behind the counter why one of them is missing. His response? “Oh, a delivery truck ran into that beam at the corner and broke it.” So it goes.

The original locations were—and still are—excellent

The Circle K team excelled at site selection from day one. Their original set of markets were typically built on either mid-tier hard corners or midblock just off main streets, but always square in the path of suburban growth. Auto dependent housing developments, both existing and future, were never more than a few blocks away, perfect for a drive-in model that relied on quick accessibility and convenience. Neighborhood adjacent, plenty of traffic count, and just speculative enough to extract some extra value—their early locations checked every box.

1802 E. McDowell via 1969 aerial. Close to middle-class, single-family neighborhoods and at corner where major arterial meets relatively minor residential collector.

An implicit endorsement of their former locations, modern Circle Ks often live just a block or two away from the buildings they once occupied but later abandoned. The new locations, however, reflect adjusted business models (on-site fuel pumps etc.) and the ability of a now major corporate company to afford a higher tier of hard corner.

3531 W. Bethany Home, built in roughly 1963 and now home to Llantera Tire Shop, is a quick three-minute walk to the Circle K at 5849 N. 35th Avenue, which is great news for anybody on lunch break who’s jonesing for a soda.

8040 W. Thomas Road, built in roughly 1961 and now home to Cactus Food Mart, is a bit closer even. Just a two-minute stroll to 8001 E. Thomas Road, a twenty-year-old Circle K that’s set up with not one, but two sets of fuel pumps.

1101 E. Indian School Road, built in roughly 1966 and now home to SAS Too (2010).

Interestingly, Phoenix’s first Circle K, the one at 16th St. and Roosevelt that offended neighbors on account of its proposed liquor sales, had such a prime inaugural location that, rather than let the original building be released back into the wild, the corporation tore it down around 1985 and replaced it with a new, fuel-equipped store.

1001 N. 16th Street, where it all started for Phoenix, circa 1976.

1001 N. 16th Street seen here in 1986 just after it replaced the first Phoenix Circle K location.

Led by their allegiance to an ever-updating business model, Circle K has decided a thousand times over whether to retain, release, or rebuild an aging location. As a result, and in a strange twist of irony, the company actually least likely to reuse a midcentury Circle K may very well be Circle K itself. But where the corporation sees a liability, wild-eyed entrepreneurs, not unlike the very ones who founded Circle K so long ago, continue to see an opportunity. Thanks to buildings that are right-sized, easily altered, and well-located, those entrepreneurs are often proven right.

Keeping Strange Things Afoot

"You might be a king or a little street sweeper, but sooner or later you dance with the reaper.

-Grim Reaper, 1991

At a cabin in the mountains of Colorado, somebody once told me the key to success. They said it to everyone in the room, just gave it away and didn’t charge a soul or even ask for an autograph afterward. They said, “It’s simple. You gotta increase your luck surface area.” And after a few years of thinking about it, I’m pretty certain the same goes for buildings.

The luck surface area phenomenon is why so many old Circle Ks get reused. It’s also why well-intentioned preservationists take the wrong approach when they show up to public meetings with demands, rather than business models. We shouldn’t ask how we can protect more buildings. Instead, we should ask things like: How do we increase the number of successful local businesses? Or, how do we make buildings easier and cheaper to reuse?

In the end, it is a pragmatic calculation. Businesses need buildings, and they will find and fill the ones that stand out as especially useful and adaptive. Thus, if you lower the barriers to reuse, if you increase the luck surface area of a given building, then over the course of a large enough set of buildings the entrepreneurs will follow, saving a few more than they knockdown. Not because they are suddenly converted to some zealous belief in historic preservation, but because they seek the path of least resistance, like water finding its way downhill. Because the truth is historic preservation scales through adaptive reuse, not National Register applications.

1802 East McDowell continues to be an example of that path of least resistance. To whit, the bottom panel of its tall yellow sign recently changed. One day it was skeletal and empty, and the next day it was there: Dima’s Fusion Grill - Middle Eastern Tacos and Mexican Food. Another new venture incubated out of an old building. Another entrepreneur in the back, experimenting like a business model mad scientist.

And who knows? Maybe they’ll work hard and they’ll get lucky and they’ll sling enough tacos to keep the place humming for another couple decades, until the next risk-taker comes along, and we do it all over again.

Sources

[1] Arizona Republic (Phoenix), April 2, 1965. p 23.

[2] Arizona Republic (Phoenix), November 17, 1979. p 5.

[3] Arizona Republic (Phoenix), June 25, 1985. p 32.

[4] Arizona Republic (Phoenix), February 25, 1991. p 13.

[5] Arizona Republic (Phoenix), April 24, 1957. p 4.

[6] Arizona Republic (Phoenix), September 1, 1957. p 21.

[7] Arizona Republic (Phoenix), December 29, 1957. p 64.

[8] ibid.

[9] Carol Willis, Form Follows Finance: Skycrapers and Skylines in New York and Chicago. Princeton Architectural Press. 1995. p 10.

[10] Willis (n 9), 10

[11] Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning From Las Vegas. The MIT Press. 1972. pp 6-9.

[12] Venturi (n 11), p 9

[13] Arizona Republic (Phoenix), February 2, 1969. p 38.

[14] The New York Times (New York City), December 6, 1991. p 4.

[15] Willis (n 9), pp 19, 23.

[16] Nancy Levison, Re-inhabited Circle Ks, Places Journal. September 2009.

[17] Stewart Brand, How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built. Penguin Books. 1994. p 190.

[18] Brand (n 17), p 192